Chrononutrition : Myth or scientific reality?

Source: Nutriactis/Rouen-Normandy University Hospital

Chrononutrition, a concept introduced in 1986 by Dr. Alain Delabos, is based on adapting our diet to our biological clock (circadian rhythm), considering the timing of our meals throughout the day.

In this newsletter, we invite you to better understand chrononutrition, explore how the circadian rhythm works, and discover what science says about it. Don’t forget to take on our challenge on the last page.

Circadian rhythm: the biological clock of our body

Origin

“Circadian” comes from the Latin circa (“around”) and dies (“day”).

Definition

The circadian rhythm is a biological cycle of about 24 hours that regulates sleep–wake cycles.

Brain clock

This rhythm is controlled by a “central clock” located in the brain (the suprachiasmatic nucleus), which synchronizes peripheral clocks (organs).

Functions

It regulates many behavioral and physiological processes: wakefulness/ sleep, fasting/ feeding, body temperature, hormone secretion, digestion, etc.

“Zeitgebers”: définition

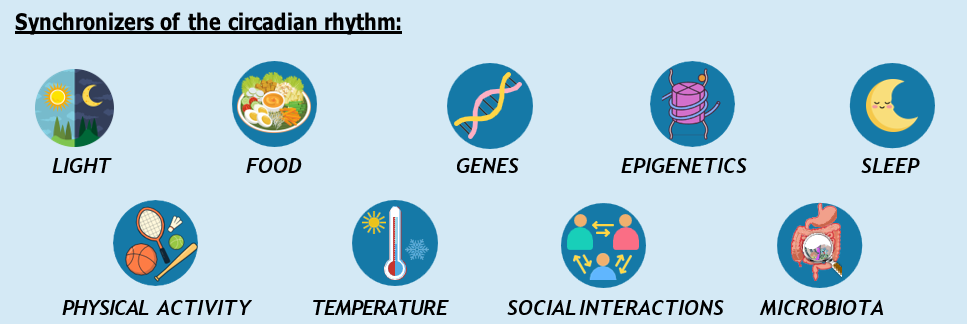

“Zeitgebers” are environmental and social signals that inform the circadian system and continuously synchronize biological rhythms over 24 hours. Daylight is the main zeitgeber, and food intake is also a powerful synchronizer.

Circadian desynchronization

When our rhythms no longer align

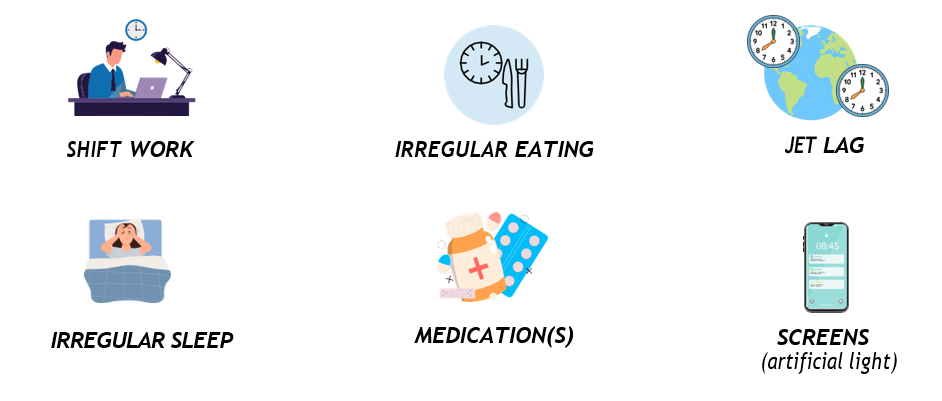

Circadian desynchronization refers to a misalignment between the internal biological rhythm (circadian rhythm) and external factors that usually regulate it, such as the light–dark cycle, sleep schedules, meals, or social and professional activities. Circadian disorders often manifest as an abnormal distribution of sleep over 24 hours.

Desynchronizers

Circadian desynchronization can be triggered by various internal factors (e.g., pathology, stress) as well as external factors such as:

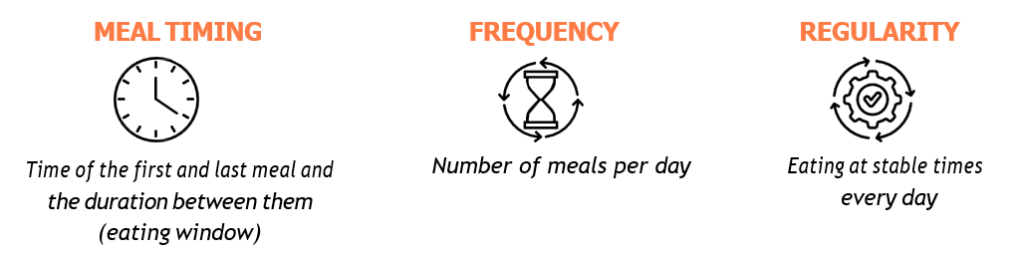

The pillars of chrononutrition

Chrononutrition is based on the principle that our body follows a circadian rhythm and therefore does not respond in the same way to food depending on the time of day, due to fluctuations in metabolic, hormonal, and digestive systems. It is based on three dimensions of eating behavior:

Impact of chrononutrition: what science says

Breakfast

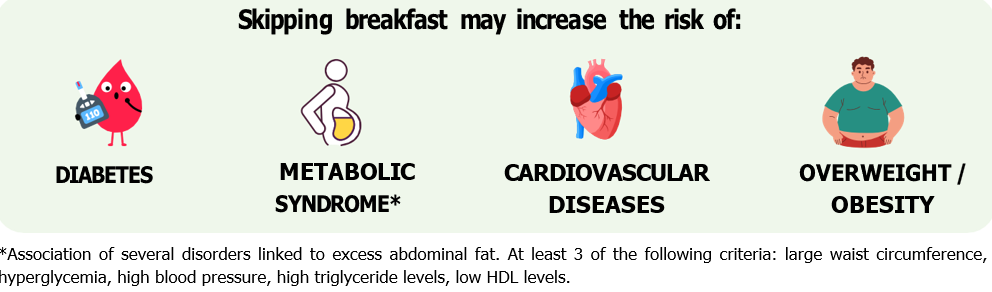

Studies highlight that skipping breakfast or eating it late may have negative health consequences by disrupting glycemic and lipid regulation and increasing the risk of low-grade inflammation. These risks may also be associated with a late dinner (less than 2 hours before bedtime).

Warning: Some studies suggest that a late breakfast could, in certain cases (diabetes), improve fasting blood glucose, indicating that the effect may vary depending on health status.

Lunch

Some scientific studies suggest that an energy distribution favoring an earlier lunch (rather than a late one) could be associated with a reduced risk of diabetes and improved lipid regulation.

In people with overweight or obesity undergoing weight-loss management, eating lunch earlier (before 3 p.m.) could promote weight loss and reduce the risk of diabetes, independently of calorie intake and physical activity.

Warning: However, the overall quality of the evidence remains limited, as studies present a risk of bias and sometimes contradictory results. Further research with longer follow-up, larger populations, and comparable protocols is needed

Dinner

Many studies point out that a late last meal—after 8 p.m. and/or less than 2 hours before bedtime— could be associated with an increased risk of:

These risks could be explained by the fact that eating late in the evening may increase feelings of hunger by modulating appetite hormones (↑ ghrelin/leptin ratio), while slowing metabolism and promoting fat storage (↓ lipolysis and ↑ adipogenesis).

Conclusion

Research in chrononutrition suggests that eating earlier in the day—breakfast, lunch, and dinner— and maintaining regular meal times could have beneficial effects on the body. However, three essential points should be emphasized:

- These potential benefits can only occur within the context of a balanced and varied diet.

- Evidence remains limited and sometimes contradictory, hence the need for longer and more robust studies to confirm these effects.

- Before making major changes to your eating habits, it is recommended to discuss them with a healthcare professional.

-

Chrononutrition: myth or scientific reality?

pdf – 2 MB